Ghost Story: David Berman

Reflecting on Silver Jews, addiction, religion, and the Memphis-Nashville rivalry as we near the fifth anniversary of Berman's death

I’d always considered David Berman an enigma. We had a few friends in common, and I’d immersed myself in his music ever since I’d stumbled across a copy of the first Silver Jews release, a seven-inch record called Dime Map of the Reef, at Shangri-la Records, which, for the 1990s, was Memphis’ sole independent record shop—and, for much of that decade, my workplace. In those heady, early days of the independent music scene, anything seemed possible, and I was ecstatic when, in mid-1994, I heard that Berman had arrived in Memphis with his friends and fellow bandmates Steve Malkmus, Steve West, and Bob Nastanovich in tow to record the Silver Jews’ first full-length, Starlite Walker, at Easley-McCain Recording Studio.

I spent a lot of time at that studio, both before I began working at Shangri-la, and during my tenure there. Previously, I worked at Kinko’s, making endless photocopies on the 5330 under impossibly bright florescent lights. I’d clock out at 11 p.m., pick up a six-pack, and head to the studio, which was located just past the southeastern edge of Midtown. Doug Easley and Davis McCain are kind friends a half-generation older than me, and they were like cool older cousins who I strove to emulate. For multiple reasons, I was restless and eternally frustrated back then. The only place I felt truly comfortable was on the couch in the back of the control room. I was a quiet intruder, and helpful as needed. I could take a band like Sonic Youth to Graceland Too and Junior Kimbrough’s juke joint without losing my cool. Ha—I’m still unsure who was doing who a favor here. The studio was exciting, but also an extremely chill environment. A steady stream of out-of-town bands, many from Matador Records, found their way to Easley-McCain, augmenting the local indie groups who booked recording time. I turned up for sessions by Cat Power, Guided By Voices, and the Spinanes. I also brought in musicians recording for Sugar Ditch, the seven-inch vinyl label I started with Gina Barker and Luther Dickinson. The Simpletones, Ross Johnson, ‘68 Comeback, and Hot Monkey all cut their sides at Easley-McCain.

Despite all that, I wasn’t around for any Silver Jews’ sessions, which were closed to visitors. Like everyone else, I had to patiently await the final product, pressed up by the ethereally cool Chicago label Drag City. By the time Starlite Walker arrived in the bins at Shangri-la, Berman’s backing musicians were rocketing to stardom as Pavement. I was certainly a fan, but I preferred the heavy American lit references rendered via Berman’s deadpan baritone delivery and the sing-a-long choruses that marked Silver Jews’ material as a little more cerebral, a little bit different. When Berman and company returned to Memphis for what would ultimately be an abortive attempt to record a follow-up, I’d already burned through three vinyl copies of Starlite Walker.

My suspicions were confirmed when Berman’s poetry was published and lauded by aesthetes such as Open City, The Baffler, and the New Yorker: the man was climbing the rungs from the low-fi music movement to high society, and I rejoiced in it. “One of us,” I marveled, hyped by the thought that someone who had hung out at the same studio I did was creating work worthy of such accolades. As a lifelong reader, I rejoiced at the idea that Berman viewed rock’n’roll as a detour, not a dead end. Then, after Berman put New York behind him, left the writing program at the University of Massachusetts, and abandoned his birthplace in Virginia for residency in my home state, word started floating back to Memphis. Berman was living in Nashville, and he’d flipped out. Berman was snorting endless amounts of coke, shooting speedballs, smoking crack. Berman attempted suicide. Then, finally, Berman was in rehab, had reclaimed his Judaism, and was ready to live again.

In mid-2008, J.C. Gabel, my editor at Stop Smiling, asked if I’d travel to Nashville to interview a sober Berman for the magazine’s thirty-eighth issue. When I got the assignment, I had no idea what to expect. Four years had passed between the release of Silver Jews’ fourth album, Bright Flight, and their fifth, Tanglewood Numbers. Nearly three more years had elapsed before Berman re-entered the recording studio for Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea, which was released that June. I knew Berman’s recordings intimately, but had never met him face-to-face. A firm believer in the “kill your idols” philosophy of fandom, I warily loaded up my car stereo with my collection of Silver Jews CDs, and pointed myself east, driving two hundred miles to Berman’s driveway. I found a piece of paper with my name scrawled on it taped to his mailbox, and I removed it and went inside.

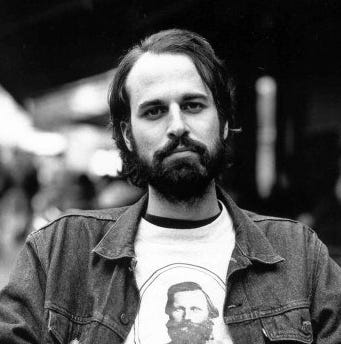

Berman immediately put me at ease, escorting me to his den, which was decorated with a framed map and floor-to-ceiling bookshelves. He looked and sounded the part of a twenty-first century Jewish scholar—rangy but pale, wearing tinted prescription glasses and a pair of well-worn blue jeans, his dark hair grazing the collar of his oxford-cloth shirt as he bent to select theology texts that illustrated our conversational points. A handsome dog plopped on the floor, content to gnaw on a menorah-shaped squeaky toy as we talked. Hours passed, and the sun was low in the sky when I left.

photo credit: Edd Westmacott/Photoshot/Getty Images

Lookout Mountain, Lookout Sea is your sixth album in nineteen years. Has your relationship with the business of music changed over the last two decades?

The older you get it’s harder for an adult ego, I think—or for dignity—to handle the critics. Everybody is an expert on cantors; everybody is an expert on singers. I work in a field where anybody of any age or race can legitimately tell me I suck. Whatever you think you were put on earth to do, [it] is “stupid”, “gay”, “ugly”, whatever.

Criticism is everywhere now. On the Internet, people are rating washing machines and plastic surgeons.

This is what I did for this album: to prevent what I hate, which is the blurb reviews that are, “used the same influences, et cetera,” I thought, well, what if I got some people I knew who didn’t regularly write rock reviews write reviews of this album. I picked some good writers who would use original thought and really engage with what’s there. I wrote these guys a blind letter, and I said I need some help from some writers. I don’t need any value judgments – there’s already so much king making and easy praise. I just wanted someone to listen to the songs, think about ‘em, and see if there’s any connection between them.

It’s almost like I’m trying quite obviously to get around something, and it’s the big, dumb thing in the middle. There are smart people around the edges, yet I often feel culturally superior to people… like, say, college newspaper editors. That’s where the indignity comes in—the superciliousness and the smugness playing out of American ignorance.

So you hate being pigeonholed.

Yeah, because it might obviously be the wrong place to go. You get just two or three signifiers per band. The writing that’s been done about Dinosaur, Jr. over the years gets impoverished by quotes like “stoner, hair in face, blah blah blah” and [J. Mascis] plays that up. It all becomes one, which is part of the problem. All of those bands in Melody Maker have figured out what they are from the critics. It starts a loop. Like Loop, the band—it happened to them!

I’ve always felt outside of poetry, outside of music, outside of Jews, outside of Gentiles, outside of southern culture, outside of everything. I wanted to be outside of academia and so I moved into popular art because I felt like I could get a bigger audience by branching out. Maybe five or ten thousand people would read a book of poetry, but maybe I could get to thirty or forty thousand people through music.

But at this point, I’m starting to feel like it might not be such a bad idea to contextualize back the other way. I’m not feeling comfortable calling what I’m doing the same thing as what Radiohead is doing. To me, thinking that Radiohead has anything to do with what I do is crazy! We both make sounds, but there’s a totally different thing going on there. It’s as foreign as Christianity itself—I’d have to have a different cosmological view of the world to think what they do is important.

Is it hard to relinquish your songs, to let go of your work and allow it to mean something else for someone else? I think with Starlite Walker and even later albums, your songs have struck chords with certain people and become iconic soundtracks for their lives.

No, I want it to happen. Take the new album. There are sixteen chords total on it, and they’re listed in the liner notes. Anybody can play these songs. If you have two hands and you take a couple of hours to put those fingers on those dots and strum, you could figure it out. To me it became a great metaphor. It’s turned my limitations—the fact that I don’t know many chords, that I don’t move my hands up the guitar neck, and that I have a simple voice—into a plus. Not only do I want people to take the recorded versions of these songs in their lives, but I would love people to take the songs into their instruments. It’s such an obvious thing, although you never see a rock band doing this.

Perhaps it’s like revealing a magic trick.

To a degree that’s true. Maybe I don’t want other people to know how easy this is. I’m not the type to spout on about teaching a man to fish, but it does amuse me that there’s such a conversation about giving away music. What people are talking about is giving away recordings. But maybe there’s a lucrative deviousness to it. Maybe these kids will grow up to have cover bands, and they’ll play my songs on their records.

Now you’re thinking like a Nashville musician!

One thing that’s so obviously great about Tennessee is that there are two American cities here—Memphis and Nashville—where art has triumphed. In neither place, not in the 1920s, ‘30s, ‘40s, ‘50s, or ‘60s, did the city fathers hope that their city’s legacy would be as a rockin’ town. When there’s a Tootsie’s [Orchid Lounge, a legendary Nashville bar] in the airport, it gets a little corny, but there’s something else to it. Even in the shitty local bands, the kids play better.

Nashville honors verbal imagination. The living presence of the past gives me a lot of pleasure. I really enjoy walking down the street where Dallas Frazier got the idea for “Elvira”, or walking by Pee Wee King’s mother-in-law’s house. People are open to humor and sadness and the co-existence of those two things. It’s such a strange place… Tennessee is a bizarre situation: the no horse racing, which is a good thing to me, and furthermore, no gambling. We have a lottery now, which I hate. There was an argument in the paper about whether it was a regressive tax on the poor. The other argument is, do we want to stand in line at the convenience store for a pack of gum behind a guy buying Lotto tickets?

From my perspective, Memphis is so alienated from Nashville.

That might be true, on a racial level, with East Tennessee.

We’re the redheaded stepchild of the state!

For the record Tanglewood Numbers, I used an Eggleston photograph, from Memphis, on the album cover. The middle of the record says, “Made in Nashville.” On the back cover, there’s a picture of Signal Mountain. The initials of the record title are “TN.” Things like that lucked out. There are a million things like that with this new album. That’s why I wanted to give it to real writers first, to see if they’d see it, too.

You’ve lived in Tennessee for what, a decade?

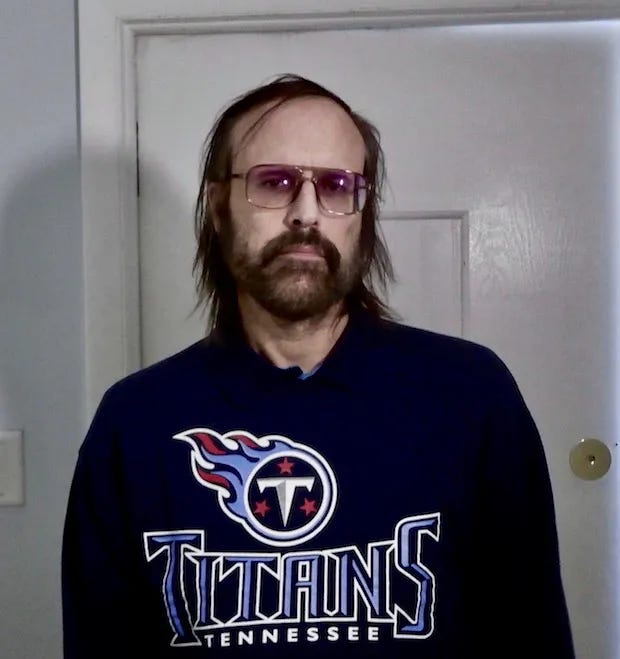

We moved to Nashville in ’99, on the day of the very first Titans game, which is another point of bitterness I don’t want to bring up! [Laughs] It was the greatest NFL season. I was fascinated by the idea of being the fan of a team in year zero. I could live here fifty years and be a fan for fifty years—it seemed really cool. It was also the fall before Y2K. Dan [Koretsky] at Drag City was going batty, and I think he wanted to move everything down here because he had some theory… We had scouted Nashville from Louisville, but we didn’t know anyone down here. We drove down and found a place for $1000 a month, and we lived there for seven years. I paid seventy thousand dollars at the end of it, and I thought, holy moley. My wife Cassie was like, “David, we can buy a house for less than this.” Of course, when you move somewhere, you don’t know you’re gonna live there ten years.

photo credit: Michael Schmelling

How did you and Cassie meet?

I was a party in Louisville after the Breeder’s Cup in November ’98. I wasn’t living anywhere. I was driving through town and staying with my friend Bob [Nastanovich]. He took me to a Thanksgiving party where someone was talking about the prettiest girl in Louisville. They pointed her out to me, and I was in this nothing-to-lose mode. For the first time in my life, I’d go up and start conversations with women I didn’t know. So, with incredible luck as it turned out, we went back to her house and she had all the Silver Jews records. I had to let down my rationale and my suspicions and go, “It’s meant to be.”

Let’s talk religion. Is it ironic that you conjured up the name Silver Jews, now that you’ve embraced Judaism? Or was it also “meant to be”?

The term “Silver Jews” means two things. First, it describes the arc of what I was doing with words, starting when I was twenty-two or so. The culture in 1990 was such that absurdity was preferred, particularly with the music that I listened to when I was working as a guard at the Whitney. The band was a conceptual project that came from sitting around the museum. I must’ve thought to myself a hundred times, what would be different if I hadn’t picked that name? What kind of millstone has this been around my neck? I would never forgo it, though—I feel like “Silver Jews” took on meaning for me years after I came up with it. It’s intense, like Phillip K. Dick saying, “I wrote this short story, and it came true.”

I’m not a Jew; I’m a “Silver Jew”. My whole life, I never wanted to be part of any group until a couple of years ago when I wanted to be a Jew. Growing up, I was always aware that to an orthodox Jew and most conservatives and to the government of Israel, I’m not a Jew. My mother converted before I was born, but her blood isn’t Jewish, and she’s no longer practicing anyways. I realized, “silver” means secondary, and it all started to make sense to me. Being like that with the Jews is a weird, very novel thing. For thousands of years, nobody wanted to be a Jew! Nobody felt bad about being rejected! That’s new to me—wanting, but not being able, to be something. Here I am and I can’t get in. It’s a very strange existential position. The world’s most despised don’t really want me!

That really inspired me. Before, instead of feeling really wishy-washy about what I was, it gave me a good idea of who I was and what I could be. Let’s say I am following the Jewish people. When they went across the Red Sea, there were all these stragglers behind them, as they describe it in Exodus. Maybe I’m one of those. I’m free of all the mitzvah. I’ve developed a program for myself, which has to do with reading a lot. There’s so much to read, the stuff slips right out of your mind. It’s like reading a self-improvement book—you can underline stuff, but you’d better go back and read it every day. You know, in Jewish culture, fathers proudly marry their daughters off to the sickliest scholar in town. That makes it a good religion for me, because I love to read!

In regards to the Torah, there are thousands of years of commentary, which boils down to the mystical stuff about being humble and being conscious of God’s presence and God’s will. When I got sober I realized the relief of it: There’s not one thing in the world that I should be doing that I’m not doing right now. I’d always had a completely exploded relationship with the things I wanted and needed to do. There’s a pleasure I would get for the first couple of years [of sobriety]—driving around and seeing a police car, for instance. There would be panic at first, and then the pleasure and release of knowing I’m not carrying any drugs. I had no idea I was in so much pain driving around all those years. I couldn’t believe it. I could feel, all of a sudden, what someone should feel in a society if they’re not breaking the law.

photo credit: Kylie Wright

Would the twenty year old David Berman have voted the thirty year old David Berman the world’s most unlikely person to smoke crack, or have expected to attempt suicide at 36?

No, because when I was twenty, I was smoking PCP! Maybe I didn’t think I would go to crack, or to needles. The worst part of going down that far is the people I wound up with at the very bottom, at times when I was participating in complete misery. I remember going up with this guy to some apartment where his grandpa lived. There were five people watching TV in the living room, all out of drugs. We went into the room where his grandpa was, because we didn’t want to smoke in front of them, and we sat beside grandpa on the bed. I swear to God, he had an oxygen tank. We smoked, and I didn’t really blink an eye when he handed it over to grandpa and he smoked. I live in fear of seeing those people around... I went to two shows recently, the first shows I’ve gone to in a long time. I don’t wanna hear, “Where you been?” I feel the pressure. When I go out to a club and see people from the past, there’s an unbearable specificity that I can’t handle. I want to be humble like I am at home, where I’m transparent. I can’t have those relationships again. One of my best friends in town is [filmmaker] Harmony Korine. We’ve only known each other since we got out of rehab. He wasn’t as mean as I was, I guess, but he was a lot weirder. We hear the stories about each other, and we can't believe it. He's the nicest person in the world, and apparently he thinks I'm not an asshole!

All of the clichés are true. You can’t know how good life can be until you stop long enough to see, which takes awhile. When I was using, I had no humility at all. What I did to my wife was one of the worst things that could be done to anybody—especially to someone who’s so wonderful in every single way. I tried to write a suicide note to her, which was just terrible. She showed it to me. It was bad writing. I was the most boring person in the world, and I had nothing final to say… I choose to believe some things that may seem mystical to others, but I consider it possible that I died and that this could be a parallel universe.

I almost got hit by an eighteen-wheeler once. It brushed passed my eyelashes, and for the next two weeks I was convinced that I’d died, and I was actually in limbo.

What if, after that, everything you ever wanted started happening? It would be even more convincing. My comeback is always, “But then I would have better teeth!” Another conclusion is that life can be operated. That’s why I like Judaism, which has this perspective of survival. It’s like looking at the empires who have reigned over history, and deciding to bet on the one I’ve watched almost get stamped out so many times and still come on. If any religion is hooked up to the truths of the universe, they’re the one. You know, I could convert. The rabbis have to treat a convert as holy as anybody else. I don’t want that, though, because I associate that with the protection that a Christian tries to achieve through believing.

I used to work for Ike Turner, and he would wear a crucifix and a Star of David at all times.

That’s covering your bases!

When you were using, were people around you aware?

Definitely! There was this crackhead, an older guy who was an ex-soundman for Jimmy Reeves. He had a lot of energy, and he moved into a printing shop, which he was trying to turn into a club. On the outside, it was all boarded up, but inside, there was a stage and lights, a big soundboard and even a fog machine. It was pitch black in there, always night. I used to get powder from him, and I started hanging out there. He had the Tennessee EP on his desk and some hooker would come in and he’d go, “That’s him! Look!” I would be there for days, smoking, and I would actually get up onstage. It was the first stage I ever hung out on. Mostly, I’d blast music in this big cavernous club. It was such a bizarre, endless night.

Some weird things happened… This friend of mine, Sweet Dog, who worked for Fat Possum Records, came through town with Paul “Wine” Jones. They played at the End, and it was great, but I was mad there weren’t more people there, so I said, “You have to play again! I know this club downtown!” They were up for it, so they set up at four in the morning. I was having such a good time I started swinging from this rafter and I fell, “not like a cat,” as Sweet Dog said. When I got out of rehab on January 1, 2004, he sent me a big box with a hundred Fat Possum CDs in it. It was actually the best gift you can give somebody coming out of rehab. You’re coming out, you’ve got no dopamine in your head, you’re just a shell of a person, you’ve got everybody mad at you, and you could use a box of Fat Possum. It’s like a hit bottom gift basket!

How did you kick?

After I tried to commit suicide, I woke up in Vanderbilt’s psych ward. The first half-day, I didn’t even realize who I was. I was just a zombie on Phenobarbital. There was this guy in there, my roommate, who had been at Vanderbilt in the heart hospital a year before, and he’d been given a heart transplant. They knew him around the hospital, and he had really disappointed everyone because he had gone back after his heart transplant and started smoking again. He was hitting the pipe on a thirteen-year old girl’s heart. When he started to freak out with cocaine psychosis, he was trying to rip open his chest and get the heart out because he was convinced that the FBI and the CIA had bugged it. That’s the bottom. Immediately, I was forced to consider, “Am I like this?” My wife begged me to go to Hazelden. It sounded like a prep school, but I went along with it. That year, I stayed sober for three months, then I relapsed three times. I had a couple of beers during the making of Tanglewood Numbers, and that was the end.

When you started using, were you depressed? Musically, you’d achieved cult figure status, and your poetry had been published and gotten rave reviews…

I had achievements, but in general, my esteem was pretty low. Maybe I was trying to be uncompetitive, when I really am a competitive person. I was definitely majorly medicated on antidepressants. I was on ‘em at sixteen, then not again until my thirties, when the drinking and the drugs were so punishing to my brain that I needed to be on [selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors]. Clearly when I got off the drugs, I had to stay on antidepressants because I still needed the boost. I still take them, and I take large amounts of them. I like to talk about it. I understand that the drug companies are sinister and evil, and I also understand that nobody wants people to start experimenting with happy pills. But because there’s such a disposition to mistrust antidepressants, I’m always pissed off that people I know who need them won’t take them. Sure, people used to not need antidepressants, but no one’s ever lived in a place like this. I think SSRIs repair your brain. I’ve said to friends of mine, “Try ‘em just for a year, to remember what it feels like. Just to get you going.” No one wants to say, “Hey, I’m on antidepressants!” But if anyone’s worried about it affecting their creativity, I’ll issue a challenge—if you like the Silver Jews, listen to the new album. Then listen to someone else who’s not on SSRIs. Listen to their latest album, and decide for yourself.

You just mentioned low self-esteem. Is that what was going on when you came to Memphis in 1995 to record the follow-up to Starlite Walker at Easley-McCain Recording Studio, then split in the middle of the night?

That was a nightmare! I came down from Virginia. Malkmus and Bob and Steve West were coming from a Pavement tour, and we met in Memphis. First of all, I couldn’t find a place to stay. With no exaggeration, it seemed impossible. I could’ve call Drag City and have them figure out hotel rooms for everybody, but I couldn’t spend that money. We’d needed three hotel rooms at eighty dollars apiece for six days, and at that point, the way I thought about money, I couldn’t spend it. I was a terrible decision maker, and so we ended up at this seedy hotel that was right off the road you come in on from Holly Springs [Mississippi].

L-R": Stephen Malkmus, David Berman, Bob Nastanovich

That’s Lamar Avenue. One of the motels on that stretch is the Rebel Inn, where James Earl Ray stayed when he came to Memphis to assassinate MLK.

Oh my god! It wasn’t that place, but I remember it. I said, so we’re gonna stay in this place, and then we went to the studio. There was some Australian girl following Pavement who was a pain in the ass. She got a room at the hotel, and locked herself in. Malkmus was in a mood I couldn’t handle, maybe his cockiest mood ever. I remember being in the vocal booth at Easley thinking, I can’t do this. I felt like Starlite Walker was a fluke. I had this intense desire to flee. All the guys were justifiably saying, “We came down here for this. You can’t just go home.” Bob couldn’t understand, and Malkmus still doesn’t forgive me for flying him down on Value Jet! I remember him coming in and saying, “David, are you having some kind of nervous breakdown or something? Cool—let’s make it like Alex Chilton! Big Star’s Third!” He was joking in his way, but that was his angle. “Roky Erickson!” I was like, “Bob, call Hertz and get me a car,” and I drove back to Virginia. Bob and Steve got a real hotel, and that little girl kept calling the studio asking, “Where are you guys?” She was totally trapped, and we never checked in. Super fan!

You’ve recently overcome those negative impulses to perform live…

I think the shows have been going pretty good. It’s gotten easier, and I always feel pretty comfortable by the end of a set. I’d never played solo acoustic before, but I played the new songs in order at the Corcoran Museum in Washington, D.C. Afterwards, there was a Q&A. I realized while I was playing that I made a lot of mistakes, but I didn’t get flustered, because nobody else knew the songs. I think I had just fooled myself to believe I’m uncomfortable onstage... Playing live has changed the way I think about playing in the studio. I want the records to sound emphatic. All the Silver Jews records sell the same amount. Maybe if I yell louder, they’d sell more. Listening to playback in the studio, I’d think, oh my god, I sound like Charles Nelson Reilly. I’d get mad at the engineer, because he’d say, “That sounds good.” I needed someone with discretion in there, not some guy who had to go pick up his kids at six o’clock!

Your vocals have changed from album to album. On Tanglewood Numbers, it sounds buried in the mix. On Lookout Mountain, I hear shades of Lee Hazlewood.

This time, the way it wound up, the album was recorded over such an annoyingly long period of time. I had to do some rewriting, and there were other delays. All the vocals were done in the same studio [Beech House], but over time and under different circumstances. Will [Oldham] might produce the next record, because he’s done vocals in so many different styles and using so many different effects. I can’t get an engineer to do what I want, which is why I’ve moved around so much. There are so many biases. It’s ridiculous when you find out, for instance, that an engineer is a purist. I’m too dependent on what they can dial up for me, and oftentimes, there’s a lot of resistance.

There are so many studios in Nashville, but you don’t know where they are. The studios that advertise are the corny ones. Whether they’re too proud or don’t want to announce where they are, it’s hard to find good studios here. There’s actually a guy who lives in Jim Reeves’ house who has a studio in the basement. He knows all about the easy listening side of country music.

Do you feel that Nashville has accepted you?

As far as the town goes, yes, although I only have a few musical friends, Duane Denison and the people in my band. I always tell Dan at Drag City that it’s stupid that there’s no real record label in Nashville. Yeah, there’s John Prine’s label, but I’m talking rock’n’roll. Nashville is centrally located, and you can always get somebody to play a part, get some singer you want, and I find it ironic that there’s no label here. Also, because Nashville takes civic pride in being a music city, if Drag City was here, Dan would get invited to the Chamber of Commerce. Here, he’d be respected, where in Chicago, he doesn’t even get snow removal!

from The Baffler, June 1990

Has your family come to terms with your career?

It’s always been a question. Certain things impress them—performing at the Corcoran, for instance. My grandmother lives in Washington and that was a big deal for her, something she could tell her friends about. There’s never been an artist in my family or, as far as I know, anybody who’s even done any kind of reading… I used to be embarrassed about going to universities for a thousand bucks a shot. I didn’t want to be too involved with academia. But now I’m older and I think, look how it makes my grandma happy. Why not do it? At a certain point you have to re-contextualize. If I look at what’s possible, as far as careers go, the better way for me to go is into the vague Laurie Anderson, Lou Reed, David Byrne thing, where you’re given artistic independence. Then you don’t have to get down on your knees and kiss the alternative press’s ass. I don’t want my audience to just be college kids anymore. I know there are the longtime fans who will always be there, but I also feel like there can be new work for middle-aged people.

Well, the way that you’ve played your cards, for better or for worse, you’re in this position where you’re in demand.

I’ve never been the flavor of the month. It’s never been, “Look at that lucky rock’n’roll guy!”

Based on everything we’ve talked about, do you think your life has been predetermined?

I can only go to either the multiple worlds theory, or I dunno, maybe this is what humility is. I never thought I’d be in the same magazine as a Richard Ford interview, or something. In the music world, I’m glad I think my latest record is good, and that it’s more interesting than most of the other records I see. Take the song “What Is Not But Could Be If”—I’m sure the attitude of that song is everything I’ve picked up from the Torah, which is precisely the attitude of Jewish creation, of everything coming out of emptiness…

I’ve had friends who were suicidal, and I want some guarantee from them that they’ll hang on, because I feel like I’m proof to the fact that there are second acts. There is reintegration. According to the Jewish perspective, disintegration is a function of the beginning. It’s just one step back. Look at the classic moment in Exodus when the Jews are backed up against the sea and the Egyptians are bearing down on them. The sea doesn’t part until one guy in the back, a very old man who couldn’t swim, put his foot in the water. It was definitely a case of “Fake it before you make it.” That’s a lesson I had to learn. I didn’t have faith until I saw it work through getting sober. I couldn’t believe that going through the motions would work, but it does.

All you need to do is take the first step. It’s not a fatalistic perspective, because there’s trust that your donation will be matched. Like the name “Silver Jews” taking on meaning retroactively—if I really am the first American guy who goes on tour in Germany with a band called the Jews and a violent, fiery Israeli band opening up for him, and I have to carry this name around, it’s a singular situation. I have to regard it with respect, and make sure I know what I’m doing, or I’m blowing off what could be.

Epilogue:

Unbeknownst to either of us, David Berman had fewer than eleven years left to live. During our conversation, we danced around a lot of troubling topics: his on/off relationship with his father, the corporate lobbyist Richard Berman, whose tactics he vehemently disapproved; his ongoing creative and social seclusion; the financial difficulties that, along with his addiction issues, ground down his marriage. Despite all that, I drove home from the interview feeling hopeful. It seemed, at least, that Judaism had provided a spiritual sanctuary.

However, Berman soon disavowed his religious beliefs. He also endured his mother’s death, the overdose of friend and Open City editor Robert Bingham, and the loss of veteran Nashville musician Dave Cloud. Furthermore, Berman disbanded Silver Jews in 2010, only returning to music in the months before his death with a new band, Purple Mountains. Their eponymous debut was released in July 2019. Almost immediately, it became an epitaph. Berman died by suicide on August 7. He was just 52 years old.